msn.com: This is the miracle of Gandzasar,” said Galust, pointing to a missile embedded in the 13th-century mountaintop monastery where locals say John the Baptist’s head is buried. “It hit,” said Galust, “but never exploded.”

It was difficult reconciling the loveliness of this medieval treasure’s valley location and exquisite 16-sided tambour, with the bulletholes peppering its facade. Yet given the breakaway republic of Nagorno-Karabakh’s recent history, following 70 years of Soviet atheism, the real miracle of Gandzasar is that it remains standing at all.

Nagorno nowhere

Nagorno-Karabakh, which perches like a jagged crown above northern Iran, remerged after the USSR went supernova in the early 1990s and sent breakaway Caucasus republics spiralling out of control like rudderless sputniks. Chechnya, South Ossetia and Abkhazia remain volatile. But a ceasefire between Karabakh separatists, their Armenian allies and Azerbaijan, which fought for six years over Nagorno-Karabakh, has held since 1994, allowing travellers to visit what has become a de facto (although internationally unrecognised) eastern extension of Armenia.

Stalin sowed the seeds of conflict in the region in 1921, pursuing a policy of divide-and-rule to combat ethnic opposition within the fledgling USSR. He severed predominately Christian Nagorno-Karabakh from Armenia, and spliced it to the mainly Muslim Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic. The enclave sank into anonymity until Stalin’s Machiavellian legacy came back to haunt the USSR’s disintegration, when simmering ethnic tensions resurfaced.

Cradle of Christendom

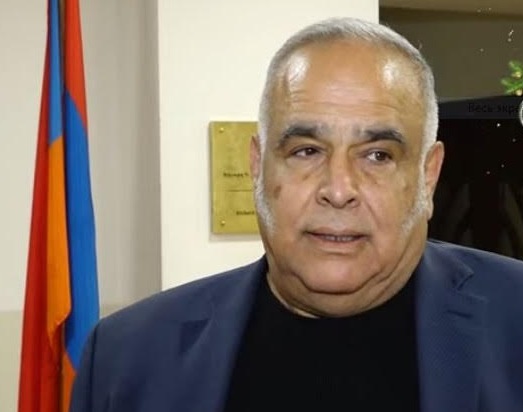

It was from Armenia’s sun-drenched capital, Yerevan, that I made the 330km drive east into Nagorno-Karabakh: the only access corridor. With me was Armenian guide, Galust Hovsepyan, whose world-weary countenance belied his encyclopaedic brilliance for history and art.

In Yerevan we visited several poignant reminders of the 1988-94 Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, such as the Mother Armenia Military Museum and Yerablur Cemetery, where 7,000 Armenians are buried from a conflict that cost 30,000 lives.

From Yerevan it was a magnificent day’s drive through the cradle of Christendom to reach Stepanakert, Nagorno-Karabakh’s capital. En route, along Armenia’s Turkish border, roadside vendors sold sweet watermelons, peaches, dried apricots and demijohns of areni wine. Behind, snow-capped Mt Ararat rose 5,137m to a summit that allegedly received Noah’s ark.

Mt Ararat was also annexed in 1921 to pacify Turkey but remains highly auspicious to Armenians. On its foothills, at Khor Virap Monastery, I clambered into a coal-black zindan (pit dungeon) where St Gregory the Illuminator spent 13 miserable years imprisoned before emerging to convert Armenia to Christianity in AD 301 – making it the world’s first Christian nation.

Beyond Ararat the road soared above 2,000m onto Syunik’s rolling golden prairie. It then entered the contentious Lachin Corridor, the umbilical cord connecting Armenia and 4,400 sq km Nagorno-Karabakh through now occupied Azerbaijan territory.

As we crossed over the River Ahavno, a border sign proclaimed ‘Welcome to the Mountainous Republic of Karabakh’. However, the locals here tend to call it Artsakh – nagorno (‘mountain’ in Russian) and karabakh (‘black garden’ in Turkic) echo years of historic foreign domination. A matter of life or death

There’s no obvious wartime hangover in modern Stepanakert, a vibrantly breezy little capital that’s been industriously reborn. A youthful population frequents airy boulevards of boutiques and cafés in a city putting down roots. Living in a ceasefire zone seemed forgotten every evening around the Armenia Hotel; on the former Soviet parade ground of Renaissance Square, goose-stepping soldiers have been superseded by promenading crowds. At 7pm I joined the nightly migration to Stepan Shahumyan Park, where a funky fountain spewed in sync to musical eclecticism – from Shostakovich to Shakira.

Stepanakert Museum holds evidence of centuries of Roman, Persian and Turkic conquest. But raven-haired museum guide, Gayaneh, was keen to reaffirm the territory’s Christian heritage, showing me khachkars, medieval memorial stones finely decorated by geometric patterning reminiscent of Celtic crosses.

When the war started, Gayaneh – then aged two – was evacuated to Yerevan. “My father was a mathematician and stayed to fight as a tank driver,” she said. This petite young woman told me she too would fight for Artsakh. It reminded me of something I’d read by Russian dissident Andrei Sakharov: ‘For Azerbaijan the issue of Karabakh is a matter of ambition; for the Armenians of Karabakh, it is a matter of life or death.’

“No country in the world recognises them,” Galust explained to us. “But the Karabakh people are very stubborn and will never leave these lands.”

Cultural corners

Over the next few days we sought out far-flung expressions of Armenian culture in the form of secreted monasteries, fortresses and ancient cities. First we visited the former capital Shushi, 10km from Stepanakert. This mountaintop fortress tops the awe-inspiring Karkar River canyon, the cliffs of which concertina into synclines as if squeezed through a cook’s icing bag. Shushi’s war-damaged streets showed glimpses of what once was an elegant multi-faith cosmopolitan city: there were Persian inscriptions, Moorish Arabian arches and the tiled minarets of 19th-century mosques. Shushi’s resident Muslim Azeri worshipped here until recently, fleeing only in 1992 after being overrun by Karabakh fighters in a ferocious battle that turned the war in the latter’s favour.

Shushi’s restored 19th-century Ghazanchetsots Cathedral highlights an interesting dichotomy. Nagorno-Karabakh’s reviving self-identity centres on its Christian heritage yet during Soviet times practising religion was forbidden so worship dwindled and churches fell into disrepair.

After visiting Gandzasar’s hilltop medieval church, we took another sublime drive to Dadivank Monastery. West of 3,340m Mrav Mountain, we skirted south of Azerbaijan’s border into the Tartar Valley’s fertile mosaic of fruit orchards and walnut groves. Here, the sparsely populated villages contained abandoned Russian T-72 tanks and defunct Soviet kolkhoz (collective farms). Indicative of the ever-present Karabakh hospitality, an old man halted his donkey to press hazelnuts into my hand with a toothless grin.

Galust hadn’t made this journey often so stopped to ask three old men seated roadside how far Dadivank was. “Fifteen kilometres,” said one. “Seventeen,” growled another. “It’s 20km!” the third exploded. “You’ve both always talked rubbish.” When we returned two hours later, the trio hadn’t budged.

Dadivank is completely unsigned and invisible from the road. Accessed by a steep track onto a mountain terrace, the terracottacoloured tenth-century building possesses the austere orthodoxy of mountainous monasteries I’d seen in Greece and the Holy Land. “It was abandoned and decayed during Soviet Azerbaijan rule. Not one rouble was spent maintaining it,” complained Galust.

But the monastery touches the very nerve-ends of Christianity. Dadi, a pupil of St Thaddeus (Jude the Apostle), is said to have travelled to Armenia two millennia ago, spreading the gospel. The church was originally built in the fourth century but rebuilt in medieval times. Its antiquated decor comprises sumptuous bas-reliefs featuring Jude and archaic Armenian script including a testament of Queen Arzou-Khatoun bemoaning her sons’ martyrdom to Turkish invaders.

Unknown world wonder?

My adventures in the South Caucasus ended around eastern Nagorno-Karabakh’s militarily imposed buffer zone within seized Azerbaijan territory. It’s accessed via Askeran, where the turreted wall of Mayraberd Fortress infills a valley like a row of yellowing dentures. It was constructed by 16th-century Persian occupiers to block access into Nagorno-Karabakh from the Caspian plains eastwards.

As I scrambled among the overgrown ruins, 75-year-old Zhora wandered out from his garden of pomegranates and black grapes. “We used to share Askeran with Azeris. We helped each other,” he said. “But it became dangerous here in 1988 when there was violence. I was born here and will never leave because my son was killed and buried here.”

Galust struggled to interpret Zhora’s dialect, which was flecked with Russian and Farsi diction. But he understood his sentiments, strident enough to suggest rapprochement with his former Azeri neighbours remained distant.

Beyond Askeran, the mountains melted into the Caspian plain stretching deep into sovereign Azerbaijan. Galust tuned in to an Azerbaijani radio station while we gazed over Agdam, an Azeri ghost town, once home to 80,000 people before being destroyed by Armenian forces. Abandoned minarets poked above the rubble of shelled buildings.

The object of our journey was Tigranakert, a 2,000-year-old city that may one day be celebrated as an ancient wonder of the world. For now though, a small museum hosts just a fraction of the treasures trickling from recent archaeological excavations. These reflect the power of Armenian king, Tigram the Great, whose once formidable empire (95-55BC) stretched from the Mediterranean to the Caspian. Marc Anthony and then seventh-century Arab invaders later occupied Tigranakert before its descent into obscurity.

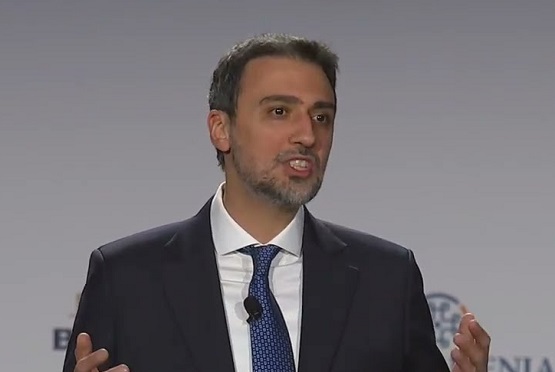

“Tigranakert is unknown because there was a Soviet prison here so it couldn’t be excavated until after the war,” explained Varham, an onsite archaeologist. Most of the artefacts, coins, weapons and tools are being catalogued in Yerevan. “The richness of these finds and this architecture demonstrates that several thousand years ago this was a major trading city between China and Arabia,” he added.

I hiked up to Tigranakert’s mountainside citadel and rested on the remains of its first-century foundations as blistering hot winds rasped the dry grass. I was totally alone bar scurrying sand lizards and looping vultures. Such a vast empire, I reflected, so completely forgotten. Then distant artillery fire from Armenian military manoeuvres jolted me back from my heat-hazed daze into the modern realpolitik of Nagorno-Karabakh.

“This status quo won’t change for some time but maybe in 20 years, when the sentiments of war have died down, there can be an agreement,” hoped Galust.

Nagorno-Karabakh remains controversial. And I was aware that, on my travels, I hadn’t heard the Azerbaijani side of the argument. But for now, this obscure breakaway republic, so rich in hospitality and history, provides an absorbing offbeat break away.